The Elizabethan and Jacobean playwrights, in heavy competition with each other, and pressurized by the need to fill the theatres, wrote fast so that new plays would be coming off the assembly line in quick succession.

As people walked past the theatres they encountered posters with the plays’ titles, and the names of the actors, many of whom were famous, as actors are today. Potential audiences would browse the posters and decide what they wanted to watch. The titles of the plays were eye-catching: they were an important selling device. They were important, as they are today. Sometimes they have a meaning, referring to a play’s theme, and sometimes they are just eye-catching. Sometimes they are both.

Ben Jonson’s titles are intriguing: A Tale of a Tub, Bartholomew Fair, The Magnetic Lady and The Devil is an Ass would be some of the titles that would assail the browser. Let’s face it, it would be hard to resist going in to see a play about the Devil or a magnetic lady.

Other titles that would beckon you in were such titles as Webster’s A Wife for a Month and The Wild Goose Chase; John Ford’s ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore and The Broken Heart, or The Roaring Girl by Middleton and Dekker.

Master Shakespeare’s plays were the most popular in London. There was no need to pull the audiences in: they didn’t care what the play was – it was the author’s name that filled the theatre. Indeed, there is hardly an interesting title among his huge body of plays. Most of them are named by the main character. It’s as though he gave the plays working titles as he was writing them and they never got changed. It’s as though, in writing Othello, he just jotted the general’s name down and when writing about a Venetian merchant he just stated that – The Merchant of Venice. Imagine this: he could have called Othello something like Brought Down by Jealousy, or Macbeth, The Over-reacher Reaches Too Far.

And then the flippant As You Like It, saying call it whatever you like. And Twelfth Night. He doesn’t come anywhere near bothering with a title for that play. It’s simply called Twelfth Night just because it was written to be performed on the twelfth night of Christmas.

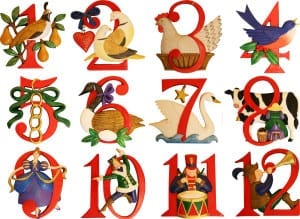

Think about the song, The Twelve Days of Christmas. We sing it quite happily at Christmas time without really knowing what it means. In our busy modern lives we have Christmas then we pack up and get back to our everyday lives. For the Elizabethans Christmas was a major festival, lasting twelve days. On the last night of the festival – the twelfth night – they had a big party then went back to work the next day. We do still have the remnants of the twelve day festival: it’s considered bad luck to take the Christmas tree down before or after the 6th of January. That’s the twelfth day – the end of the holiday.

The play was written to be performed on that last night. During the final party the Elizabethans obeyed several traditions. Cross dressing was one, drinking and carousing, another. Inversion of social roles was another, where masters waited on their servants and servants lorded it up. And lots of music and singing. The next day they woke up with hangovers and staggered off to work for another year.

And Shakespeare’s play, Twelfth Night? Well – a woman dressed as a man, the drunken revelry of Sir Toby and Sir Andrew, the songs and the music – remember the opening line, If music be the food of love play on – and the pretentions of Malvolio, the servant who has the delusion that he could become the master. It’s all very much in accordance with the themes of the twelfth night festival.

Perhaps Shakespeare’s ‘working’ titles have more to them than meets the eye?