If you’ve studied any of Shakespeare’s sonnets you may have heard of ‘iambic pentameter’… but what exactly is iambic pentameter?

Iambic Pentameter Definition

Iambic

In a line of poetry, an ‘iamb’ is a foot or beat consisting of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable.

Or another way to think of it it a short syllable followed by a long syllable. For example, deLIGHT, the SUN, forLORN, one DAY, reLEASE. English is the perfect language for iambus because of the way the stressed and unstressed syllables work. (Interestingly, the iamb sounds a little like a heartbeat).

Pentameter

‘Penta’ means five, so pentameter simply means five meters. A line of poetry written in iambic pentameter has five feet = five sets of stressed syllables and unstressed syllables.

Putting these two terms together, iambic pentameter is a line of writing that consists of ten syllables in a specific pattern of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable, or a short syllable followed by a long syllable.

5 iambs/feet of unstressed and stressed syllables – simple!

Iambic Pentameter Examples

Here are three very different examples of iambic pentameter in English poetry:

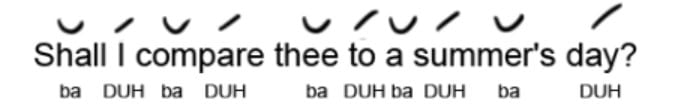

Shakespeare’s sonnet 18 starts ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’. This line of poetry has five feet, so it’s written in pentameter. And the stressing pattern is all iambs (an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable):

Shall I | compARE | thee TO | a SUM | mers DAY?

da DUM | da DUM | da DUM | da DUM | da DUM

From Shakespeare to Taylor Swift, whose #1 dance-pop single Shake It Off includes some iambic pentameter. Who knew?! (And yes, we have just classified Taylor Swift as a poet!)

I’m just gonna shake, shake, shake, shake, sha-ake

da DUM | da DUM | da DUM | da DUM | da DUM

And one final (and more traditional) example of iambic pentameter, this time from Robert Browning’s poem My Last Duchess. The poem is written as a dramatic lyric made up of rhymed couplets in iambic pentameter, with each line made up of 5 sets of alternating stressed and unstressed syllables – 10 syllables in all:

That my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Frà Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands…

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’twas not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot…

Beginning to understand it now? Check out this short tutorial

Why Do Poets Use Iambic Pentameter?

Iambic pentameter is used frequently, in verse, poetry and even pop songs. This rhythm was popularised by Elizabethan and Jacobean dramatised such as Shakespeare and John Donne, and is still used today by modern authors (read sonnet examples from other poets – some use iambic pentameters and some use other meters).

Iambic pentameter is a basic rhythm that’s pleasing to the ear and closely resembles the rhythm of everyday speech, or a heartbeat.

For playwrights, using iambic pentameter allow them to imitate everyday speech in verse. The rythm gives a less rigid, but natural flow to the text – and the dialogue. Put simply, iambic pentameter is a metrical speech rhythm that is natural to the English language. Shakespeare used iambic pentameter because it closely resembles the rhythm of everyday speech, and he no doubt wanted to imitate everyday speech in his plays.

Why Shakespeare Loved Iambic Pentameter

Common Questions About Iambic Pentameter:

Does iambic pentameter needs to be ten syllables?

Pentameter is simply penta, which means 5, meters. So a line of poetry written in pentameter has 5 feet, or 5 sets of stressed and unstressed syllables

Is ‘to be or not to be’ iambic pentameter?

No. Although there are elements of iambic pentameter throughout Hamlet’s ‘to be or not to be‘ soliloquy there are many lines with more than ten syllables, which by definition means the lines can’t be in iambic pentameter.

How can you identify iambic pentameter?

Iambic pentameter is a line of writing that consists of ten syllables in a specific pattern of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable, or a short syllable followed by a long syllable. For example ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ from Shakespeare’s sonnet 18.

This piece has been most helpful. Thanks a million for the good job.

Hope this article was helpful, thank you guys for reading!

Thank you for this tutorial. I am still trying to understand poetry. I loved it when I was at university but I never quite understood the technical aspects of it.

This has been most helpful. Thank you so much!

How can you be discussing literary devices when you are not able to distinguish “who’s” from “whose”?

I’ll explain simply: “who’s” is short form for “who is” and does not fit correctly in the sentence about Taylor Swift.

Thanks for picking up that typo Leslie! Fixed :)

that was very rude of leslie, but very well behaved and polite of you to answer so kindly Ed, I’m sure god will reward you for this🙂

Surely, you could have been couth with your observation? There was no need to speak in such a tone.

You are quite correct in your critique but the information given about iambic pentameter is also correct. I appreciate you both.

thx this was actually really helpful, unlike sm other websites i found, thx again! 😊

V helpful! Glad I found this, was suuuuper confused on my poetry assignment heehee

This was so helpful! Thank you.

A short poem of thanks utilizing iambic pentameter:

I thank you for this great tutorial.

I cannot stress how much I was in need.

I’d like to think I am mercurial;

The words struck home and knowledge was received.